BEYOND THE NUMBERS

For several decades, policy debates about cash assistance for very low-income families have focused almost exclusively on work requirements: what work activities should welfare recipients have to perform, and for how many hours, to remain eligible? These work requirements, in turn, are rooted in a basic assumption: that mothers who have never been married and who have a high school education or less — a high-poverty group that comprises the majority of cash assistance recipients — are much less likely to work than others with comparable levels of education.

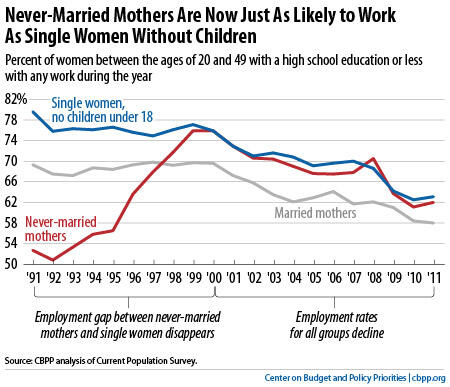

That assumption is wrong — and it’s been wrong for the last decade. Among women with a high school education or less, never-married mothers are just as likely to work as single women without children and more likely to work than married women with children. (See graph.)

The share of never-married mothers who worked jumped from 51 percent in 1992 to 76 percent in 2000, eliminating a 25 percentage-point gap between their employment rate and that of single women without children.

This sharp improvement reflected a combination of factors, including a very strong labor market (with unemployment as low as 4 percent), expansions in work supports such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and child care assistance, and welfare reform.

A highly regarded study by University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger found that the EITC (which policymakers expanded in 1990 and 1993) accounted for about 34 percent of the increase, the strong economy accounted for about 21 percent, and welfare reform accounted for about 13 percent.

Since 2000, the employment rate has fallen considerably among never-married mothers. But it’s also dropped among other women with limited education, which suggests that the causes are the economy and low education levels — not the availability of public benefits or anything particular to single mothers.

The recession hit people with a high school education or less especially hard and they are still losing ground, according to a recent report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. Women with a high school education or less lost 2 million jobs during the recession and an additional 600,000 jobs since the recovery started.

These job losses, combined with low wages in available jobs, meant that 59 percent of never-married mothers with a high school education or less lived below the poverty line in 2011. Moreover, cash benefit levels are lower, and benefits are harder to get, than ever. (Indeed, that has driven an increase in deep poverty for jobless single mothers.)

These findings suggest that if we want more single mothers with limited education to work, simply reducing welfare benefits or tightening work requirements won’t likely succeed. Instead, we need to help them compete for jobs in a period when there are three times as many job seekers as job openings — or provide jobs when jobs are not available. Possibilities include:

- Subsidized jobs. During the recession, states placed about 260,000 unemployed low-income parents and young adults in subsidized jobs — but Congress allowed the federal funding that supported these programs to expire. Transforming TANF’s Contingency Fund, which is supposed to help states respond to periods of economic distress but is poorly designed, into a Subsidized Employment Fund would be a good step towards helping unemployed single mothers find jobs.

- More access to education and training to build marketable skills. The TANF work requirements discourage participation in education and training. Policymakers should eliminate these constraints. All individuals, regardless of whether they are on welfare, should be encouraged to complete high school or earn a GED or to attend industry-based or community college programs to earn a credential that will help them qualify for better-paying, more stable jobs.

- More funding for child care. Child care is essential for single mothers — many of whom have young children — to succeed in the labor market. Yet, funding for child care and early education for low-income families is inadequate. The Child Care and Development Block Grant serves only one in six children eligible for help under federal rules, for example, and Head Start serves only 40 percent of eligible preschoolers.